Introduction

In the spring of 1969 my Science Fair project, had more to do winter weather than hurricanes. It won a few blue ribbons at the local and regional level plus a national award from the U.S. Navy (Navy Science Cruiser Award). One hundred winners from around the nation were sent for a week to a U.S. Naval Base. Fifty students went to San Diego, California, while myself and forty nine others went to Newport, Rhode Island. I arrived in Newport on a Sunday evening (August 17,1969) and we engaged in a number of activities during the week ahead. I had a strong interest in weather, but a catastrophic weather event took place far away while I was in Rhode Island. I was cut off from news and I had no idea that a Category 5 hurricane made landfall in the US.

In the late evening, Hurricane Camille made landfall near Pass Christian Mississippi. This Category 5 monster is the second strongest hurricane to strike the mainland of the United States. With wind gusts perhaps up to 200 mph and a storm surge of over 24 feet, many residents that didn’t evacuate were killed Inland, over two feet of rain killed many more in Virginia.

Transatlantic Voyage

Hurricane Camille was a “classic” Cape Verde (now called Cabo Verde) storm. On August 5, 1969, a tropical wave pushed westward off the African Coast. Atmospheric conditions weren’t favorable for strengthening and the wave continues to track westward across the Atlantic.

On August 14th, more convection (thunderstorm activity) began to appear in the vicinity of the tropical wave. On August 14th, hurricane hunters flew out to investigate. Later in the day, the aircraft found a low-level circulation and winds that were high enough to justify naming this a tropical storm. The “C” name was Camille. There is a story attached to the name that I will discuss later.

Camille was named when it was centered about 60 miles west of Grand Cayman Island as it was turning more toward the northwest. Wind shear continued to decline and that made conditions more favorable for Camille to strengthen. That’s exactly what occurred as the central pressure of Camille dropped over 40 millibars in only 24 hours.

Camille became a hurricane on the morning of the August 14th around 60 south-southeast of Pinar del Rio, Cuba, on the island’s western tip. Camille continued to rapidly intensify and Camille became a “major” Category 3 hurricane later that day.

Camille produced extensive damage in western Cuba, mainly due to heavy rain and massive flooding. Around 20,000 became homeless and there were at least five fatalities. The damage was estimated to be around five million dollars (4.4 billion 2025 dollars).

Targeting The Gulf Coast

As Camille passed over Cuba, it weakened a but everything changed in a hurry as it came back out over the Gulf of Mexico. With a track toward the northwest, Camille became stronger with maximum sustained winds of 140 mph on August 16th. As it left Cuba, the forecast track from the National Hurricane Center indicated that the forecast was for Camille to take more of a turn to the northeast and that would favor a landfall in the Florida Panhandle. Subsequent forecasts kept sliding the landfall to the west but Camille continued to track west of the updated forecasts each time.

Camille didn’t stop intensifying and on August, 17th maximum sustained winds were up to 160 mph making Camille a Category 5 hurricane. later in the day, Camille was centered about 100 miles southeast of the mouth of the Mississippi River with maximum sustained winds of an incredible 175 mph and a central pressure of 905 millibars.

New Orleans radar shows Hurricane Camille as it approached the Mississippi Coast on August 17, 1969. Image Credit- ESSA/NOAA.

Late that evening, Camille made landfall near Pass Christian, Mississippi with incredible force. All wind instruments were destroyed and all power was lost so we will never know that exact sustained winds at landfall but some estimates indicated that wind gusts could have reached 200 mph.

Gulf Coast Impacts – Wind And Surge

Camille inflicted massive amounts of damage to the barrier islands and along the Gulf Coast from Louisiana to Alabama. The storm surge along the Mississippi Coast reached an incredible 24.6 feet and inundated over 800,000 acres of land in Louisiana. Later crashed over the seawall along the Mississippi Coast and pushed over four blocks inland with tons of debris. To the east, nearly three quarters of Dauphin Island, Alabama was inundated.

Many roads, including a large section of Highway 90 along the Gulf Coast were closed for days and in some cases, weeks.

The photo shows extensive storm surge damage to highway 90 in Mississippi from Hurricane Camille in August of 1969. Photo Credit-ESSA/NOAA.

Rain and powerful winds split Ship’s Island off the Mississippi Coast and cut the Chandeleur Islands off Louisiana.

There was one “iconic” before and after photo of the Richelieu Manor Apartments that was slammed by the eyewall of Camille and the tremendous storm surge as it made landfall. There as also a story that went along with the pictures.

According to the story, 24 people held a “hurricane party” on the third floor. The story goes on to say that the storm surge destroyed the building and killed all but one person. We do know that the building was destroyed but accounts of the party are varied and it’s not clear whether there actually was a party.

This photo shows the Richelieu Manor Apartments before Hurricane Camille struck. Photo Credit-ESSA/NOAA,

This photo shows the Richelieu Manor Apartments after Hurricane Camille struck. Photo Credit-ESSA/NOAA.

There was extensive damage to homes and businesses in the vicinity of the coast in Biloxi and Gulfport in Mississippi. Hotels and restaurants were totally destroyed. Fires were fought with hard suction hoses since the fire trucks were submerged.

Many people had to move to higher floors of their homes, even well inland from the coast to avoid drowning. Some residents described a deafening wind and they could hear the sound of windows breaking all around them.

This photo shows catastrophic storm surge damage near Biloxi, Mississippi from Hurricane Camille in August of 1969. Photo Credit-NOAA.

Crop damage was extensive across southeast Mississippi with the total destruction of many pecan orchards. Crop damage across south Alabama was limited to Baldwin, Mobile, and western Washington Counties.

Pecans, soybean, and corn crops were damaged or destroyed. Pecan damage was extensive and approximately 20,000 acres of corn was flattened. It was estimated that 90% of crop damage across the area was due to the wind while 10% was due to the rain.

Total property damage for the Florida Panhandle, including beach erosion and crop losses, were estimated near 500,000 dollars (4.2 million 2025 dollars) with the major portion of the damage in Escambia and Santa Rosa Counties.

It was fortunate that rainfall totals in southern Mississippi and southeast Louisiana were held down to the 5-7 inch level because the storm was moving fairly well as it moved inland.

Over 100 fatalities were tied to the storm in the Gulf Coast region.

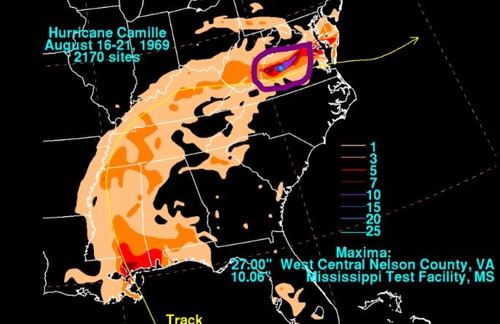

Unfortunately, the remnants of Camille dumped extremely heavy amounts of rain as it crossed the Appalachians into West Virginia and Virginia. High tropical moisture and elevation don’t mix very well. Rainfall amounts generally ranged from 12 to 20 inches over these areas. There was one report of 27 inches in Nelson County, Virginia. Much of the rain in Virginia fell in less than six hours.

Devastating Appalachian Flooding

This map indicates the rainfall totals from Hurricane Camille in August of 1969 (highlighted the excessive rain in VA). Map Credit-NOAA.

Needless to say, that kind of rainfall in a relatively short period of time can trigger extreme ash flooding along rivers and creeks in the area. Over 130 bridges were washed out and entire communities were submerged in water, especially in Nelson County and the surrounding area.

Rainfall was so heavy that reports were received of birds drowning in trees, cows floating down the Hatt Creek and of survivors having to cup hands around their mouth and nose in order to breathe.

Many rivers in Virginia and West Virginia set records for peak flood stages, causing numerous mudslides along mountainsides.

This photo shows a washed-out bridge at the Rockfish River and Route 626 (near Howardsville, Virginia) from ash flooding triggered by remnants of Hurricane Camille in August of 1969. Photo Credit-Library of Virginia.

All told, over 5,600 homes were destroyed and nearly 14,000 had major damage. There were nearly 9,000 injuries and over 150 fatalities. Overall damage was estimated to be around 140 million (1.2 billion 2025 dollars).

Aftermath

According to Wikipedia, Many federal, state, and local agencies and volunteer organizations responded in the following days. The Office of Emergency Preparedness, provided 76 million dollars to administer and coordinate disaster relief programs.

Food and shelter were available the day after the storm. On 19 August, parts of Mississippi and Louisiana were declared major disaster areas and became eligible for federal disaster relief funds. President Nixon ordered 1450 regular troops and 800 United States Army Engineers into the area to bring tons of food, vehicles, and aircraft.

Many injured residents and others who needed medical attention were airlifted to inland cities like Jackson, Mississippi.

The Federal Power Commission, which helped fully return power to affected areas by 25 November 1969. The Coast Guard (then under the Department of Transportation), Air Force, Army, Army Corps of Engineers, Navy Seabees, and Marine Corps all helped with evacuations, search and rescue, clearing debris, and distribution of food. The Department of Defense contributed $34 million and 16,500 military troops overall to the recovery. The Department of Health provided 4 million dollars towards medicine, vaccines and other health-related needs.

Odds and Ends (From NOAA)

The devastation from Hurricane Camille inspired the implementation of the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale after Gulf Coast residents commented that hurricane warnings were insufficient in conveying the expected intensity of hurricanes.

Hurricane Camille generated waves that were at least 21 meters (70 feet in height) !

Hurricane Camille created the highest storm surge recorded at that time in the Atlantic Basin at 7.5 m (24.6 feet). This measurement was based upon high water marks inside the three surviving buildings (the V.F.W. Club, the Avalon Theatre, and one house) and debris lines in Pass Christian, MS. This record value was surpassed in 2005 by the 8.47 m (27.8 feet) surge produced by Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

As evacuees returned to Mississippi, the Governor declared martial law, blocking highways into the damaged areas, creating a 6 PM to 6 AM curfew, and opening dormitories at the University of Southern Mississippi and rooms at the Robert E. Lee hotel to shelter those who lost their homes.

Camille forced the Mississippi River to flow backward from its mouth in Venice, LA to a point north of New Orleans, LA, a distance of 200 km (125 mi) along its track. From there, the river backed up an additional 190 km (120 miles) to a point north of Baton Rouge.

Like other catastrophic Category 5 hurricane, including Andrew (1992) and the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane, the diameter of Camille was relatively small, A report from reconnaissance aircraft as the hurricane was near its peak intensity indicated winds greater than 185 km/hour (greater than 115 miles per hour) just 48-65 km (20-40 miles from the eye) !

(From NWS Mobile)

August 17, 1969 (prior to landfall)

450pm – Hangar wall was blown down at the Fairhope Airport in Fairhope, AL

530pm – Tornado reported in Waynesboro, MS

600pm – Streets completely covered with water in Bayou La Batre, AL

630pm – Tornado reported in Pensacola, FL earlier in the afternoon

930pm – Violent winds observed along the coast

1000pm – 62 mph wind observed in Mobile, AL

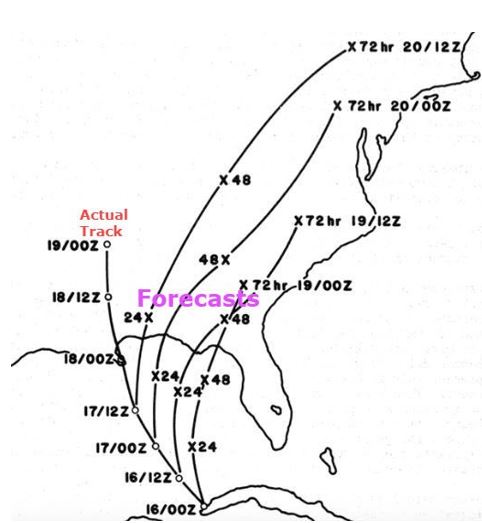

Hurricane forecasting was very hit and miss back then. There were only a couple of computer models and they were crude and not constructed to handle the tropics. I’ll show you the NHC forecasts from the time and the forecast at regular intervals thereafter (48-72 hour forecasts). Most forecasters thought that Camille would curve to the northeast and make landfall in the Florida Panhandle but Camille continues to track west of their forecast tracks. it also moved more slowly than The intensity of a subtropical high aloft as probably underestimated.

This image shows NHC forecasts for Hurricane Camille from the time it was over the western tip of Cuba. Far-left was the actual track of Camille. Image Credit- Robert Simpson-Southern Regional Technical Memorandum -WBTM.

An upper-level trough finally steered the remnants of Camille eastward through Virginia, where it became a massive flooding rain system, and into the Atlantic. Camille actually intensified to a tropical storm again once it came back over water but it continued to move away from the U.S.

There is an interesting story surrounding the name “Camille”. Other ”C” hurricanes like Carla and Carol were retired so a “C” name was needed for the 1969 season.

At that time, the senior hurricane forecaster at NHC was John Hope, who I have the privilege to work with for many years at the Weather Channel. His daughter, Camille was doing a high school project on hurricanes and long term trends and Dr. Canner Miller at NHC mentored her with the project. Dr. Miller was very impressed with Camille’s work so Camille was added to the list of hurricane names for that season (little did they know).