As this article is published, The United States is celebrating another July4th holiday. The high temperature is expected to reach the middle 80s with plenty of sunshine in Philadelphia. That temperature is warmer than it was on the original Independence Day.

In 1776, weather observations were few and far between. Weather instruments were costly and most weather observers – those who kept weather diaries, at least – were wealthy. One of them, Thomas Jefferson, kept meticulous weather records in a journal for many years.

Jefferson traveled to Philadelphia at the beginning of July 1776 to attend a meeting of the Second Continental Congress and to prepare the Declaration of Independence.

He brought his thermometer on the trip, but while he was in Philadelphia, Jefferson purchased a new one from a merchant, John Sparhawk, for a sum equivalent to $600 today.

Thomas Jefferson liked to take at least two weather observations per day. The first was around sunrise so he could log the low temperature of the day, and another was between 3 and 4 p.m. when the high temperature would be reached He would also list remarks like cloud cover, precipitation and whether or not it was humid.

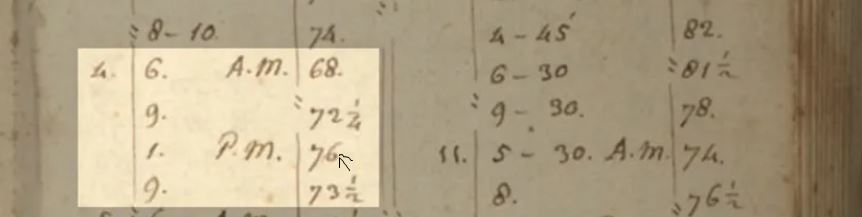

Here are Thomas Jefferson’s daily weather observations taken in Philadelphia in July 1776. Image Credit-NOAA.

Another prominent resident of Philadelphia, Phineas Pemberton, also logged daily weather conditions.

From these entries, we can formulate a picture of weather conditions during that first week of July.

According to these records, July 1st was warm and humid with temperatures well into the 80s. The day was mostly sunny, but at around 4 p.m., the sky turned dark, winds came up and thunderstorms developed around the area.

Temperatures came down a bit on July 2nd, but there were frequent showers reported. July 3rd was a pleasant, sunny day, with a high near 80 degrees.

This is the typical sequence of events you might see today with a cold front passage in summer. Warm and humid, then thunderstorms, then cooler and pleasant after the cold front moved out to sea.

Philadelphia’s Weather On July 4, 1776

The observations from Jefferson on July 4th, 1776, are shown below. Jefferson didn’t record his usual 3-4 p.m. observation, but he did at 1 p.m. He had more pressing matters that day.

A zoomed-in image of Thomas Jefferson’s weather observations from July 1776. His July 4 observations are highlighted by the square, with the time of each observation at left and the temperature (degrees Fahrenheit) on the right. Image Credit-NOAA.

The temperatures were fairly consistent with those noted by Pemberton, who recorded 71 degrees at 7 a.m. and 76 at 3 p.m.

Jefferson and Pemberton both noted clear skies and a light north wind early in the morning, then increasing cloudiness with a southwest wind in the afternoon. No rain was mentioned by either, with a high temperature of 76 degrees (quite a coincidence indeed) !

This suggests that July 4, 1776, was a pleasant summer day in Philadelphia, particularly by modern standards

Philadelphia’s average July 4th high (30-year average from 1991 through 2020 data) is 87 degrees,

Given the early morning temperature was in the upper 60s or low 70s with a light north wind, it probably wasn’t very muggy by July standards for the Mid-Atlantic.

What The Surface Weather Map Probably Looked Like

There were no hourly, much less daily, weather maps produced in the U.S. in 1776. It would be another 94 years before the invention of the telegraph and the launch of what would much later become the National Weather Service allowed weather observations to be collected and disseminated from multiple areas at one time.

Given the observations from Jefferson and Pemberton, we can form a fairly good guess at what a weather map could have looked like on July 4, 1776.

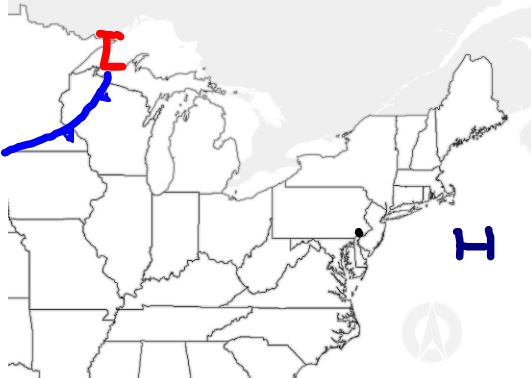

What a surface weather map might have looked like late on July 4, 1776 with low pressure far to the west and high pressure into the Atlantic. (Philadelphia is the black dot).

In Philadelphia, the wind shifted to the southwest in the afternoon. That means the high-pressure system likely moved off the Eastern Seaboard into the Atlantic, since winds around high-pressure systems flow clockwise.

There could have been another cold front west of the area, but there was no mention of rain by Jefferson until July 8, so perhaps the next front was well out to the west.

To me, its quite a coincidence that the high temperature that day was 76 degrees ! Quite fitting I would say!