On November 12, 1933, the first of the great dust storms of the 1930s hit the Dakotas. This event has been called the beginning of the “Dust Bowl” Era which lasted through much of the 1930s. The impact of these dust storms was an environmental disaster that expanded over a significant portion of the nation.

Daylight To Darkness

On November 11, 1933, an area of low pressure “Alberta Clipper” moving out of Alberta, Canada, swept southeastward. By the next morning, the low was centered around the border of Manitoba and North Dakota. The low pressure was down to 990 millibars and it continued to strengthen. A strong cold front extended to the south and southwest of the low and the system produced some light snow over North Dakota and Minnesota,

At the same time, a strong high-pressure system was building southward from western Canada, and by November 12th it was centered around the border of Idaho and Washington. The strong pressure gradient (pressure difference) created strong winds across the northern and central Great Plains.

A surface weather map for the morning of November 12, 1933. Info from DailyWeather Maps (NWS).

Because the area had just been through months of extreme drought and heat, many crops, including grass and hay, had died and the topsoil was loose, The strong winds picked up the loose topsoil, and dark clouds of dust were produced. The dust filled the sky and it was carried hundreds of miles to the east and southeast,

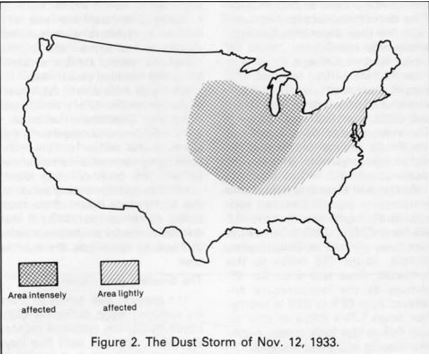

The dust storm stretched from the Canadian border to Lake Superior and southeastward Ohio. The light snowfall in North Dakota and Minnesota did help matters a bit but South Dakota received extreme impacts. The winds were relentless and terrifying.

The dust turned daylight into darkness over a large area. Crop and property loss would be estimated at several millions of (1933) dollars in South Dakota alone. There was extensive structural damage to buildings, fences were torn apart and there was damage to roadways. In Iowa, fierce winds blew hundreds of acres of corn from the stalks, visibility was extremely low, and artificial lights were required during the day. Flying schedules on the airways into the Dakotas and Canada were canceled.

A photo showing an extreme dust storm in South Dakota on November 12, 1933. Photo-Wikipedia-Public Domain

Winds forced the dust to penetrate almost through cracks in every house. The dust filtered into homes from the Dakotas and Iowa to Missouri and Illinois.

The fine dust was deposited on furniture, windowsills, and floors. In Chicago, pedestrians were gagged by the dust. Cars were stalled as dust clogged their engines. Conditions were just as bad in St. Louis.

While this was occurring, very cold air rushed into these areas behind a strong cold front. St. Louis reached 72 degrees on November 11th but behind the cold front on the 12th, the mercury fell to 27 degrees. In Chicago, the mercury fell from 68 degrees to 23 degrees.

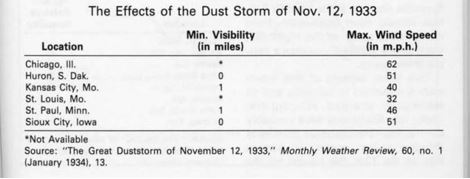

Many U.S. Weather Bureau recording stations reported zero visibility during the day. In St. Louis, the visibility was reduced to 1/4 mile, and in Chicago, fireworks set off at the World’s Fair, couldn’t be seen more than a mile or two away.

Here are some comments from U.S. Weather Bureau stations in the areas that were impacted (from AMS Monthly Weather Review).

This event initiated several years of unimaginable hardship for residents of the Plains states as a large number more similar, or even greater events, occurred in the following years.

Dust was carried eastward to the Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic and even to parts of the Southeast and southern New England, on November 12th and 13th, making for some colorful sunsets. The dust was quite noticeable in New York City.

The map indicates the extent of the dust from the November 1933 storm. Map Credit- https://gammathetaupsilon.org/the-geographicalbulletin/1980s/volume22/article5.pdf

Dust Bowl

The November 1933 wind/dust event was just the first in what was to be hundreds more events during that decade in the midsection of the nation. The storms continued intermittently through the 1030s as summers remained hot and rainfall remained low. As this extreme environmental disaster continued, the name “Dust Bowl” became a common term.

The worst impacts of the “Dust Bowl” were experienced in the central and southern Plains and westward to Colorado. Residents had to wear respiratory masks that were distributed by the Red Cross. Many had to sweep the dust out of their houses with brooms and they wet sheets were placed in doorways. Hundreds of lives were lost from respiratory illnesses from inhaling the dust.

In several of the storms, thick dust fell on Chicago and significant amounts of dust were transported to the East Coast.

In addition to the human toll, crop failures were widespread and livestock also died from inhaling the dust. All of this occurred during the Great Depression to make matters worse. Many farmers were forced out of business and they suffered extreme hardship. Around 250,000 people left their homes in the Plains and moved to western states like California to try to make a living.

A photo of an Oklahoma family preparing to leave their farm and move to California during the 1930s “Dust Bowl”. Image Credit-Pinterest

The Federal Government did take action as they sought advice from experts in agriculture. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the U.S. Congress helped to establish The Soil Erosion Service which was the first major federal commitment to the preservation of natural resources. The Prairie States Forestry Project provided a “shelter belt” from the Texas Panhandle to the Canadian border.

Through the 1930s the U.S Forestry Service, working in conjunction with the Civilian Conservation Corps, Works Progress Administration, and local farmers, planted nearly 220 million trees, creating over 18,000 miles of windbreaks on some 30,000 farms.

Significant rainfall didn’t return to the Plains until the early 1940s.