Our article last week about the “Great White Hurricane” indicated that ferocious November storms around the Great Lakes are not uncommon. This week we will look at another “iconic” Great Lakes storm that occurred exactly 48 years ago and it became notorious because of a song about a resultant tragedy. These storms became known as “Freshwater Fury”!

On the morning of November 9, 1975, an American Great Lakes freighter named the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald was preparing to leave Superior, Wisconsin, with a load of iron ore pellets that would be delivered to Detroit, Michigan, At the same time, meteorologically, a rather innocuous area of low pressure was developing over Kansas. No one could possibly know that on the next day, the two events would clash, resulting in an unbelievable tragedy with the massive ship and the crew of 29 souls laid to rest at the bottom of Lake Superior.

The story of Edmund Fitzgerald was made famous by a song written and performed by Canadian singer Gordon Lightfoot. The song was released in August of 1976 and reached number 2 on the U.S. pop charts. Lake Superior was referred to by the Chippewa Tribe as “Gitche Gumee” (Great Sea).

Background

There have been many shipwrecks on the Great Lakes over time. Some historians estimate the total to be around 25,000. Many of these have occurred during intense storms that produced incredibly high waves and reduced visibilities to zero.

The tragedy that we will describe occurred around Whitefish Bay where around 240 shipwrecks alone have occurred. As mentioned earlier, November is a month where a high percentage of these storms have occurred over time.

An alarming number of shipwrecks caused by weather on the Great Lakes and bodies of water surrounding the U.S. led to the establishment of the U.S. Weather Bureau in 1870.

A timeline issued by the National Weather Service presented the details that led to the genesis of this government agency.

The U.S. National Weather Service begins in the Department of the Army. President Ulysses Grant signed a joint resolution of Congress authorizing the Secretary of War to establish a weather service within the Army. Weather observations are made at 24 locations by the Army Signal Corps and the word “forecast” becomes established.

Several of the observation locations were on the Great Lakes.

Shipping of raw materials along the Great Lakes became a “lifeblood” of commerce in the decades that followed. Better weather forecasts reduced the number of weather-related shipwrecks on the Great Lakes but it by no means ended them.

Shipping of iron ore, obtained from mines in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan to Great Lakes ports became commonplace as many cities along the lakes had constructed steel mills. U.S. steel production increased dramatically during and after World War II.

Commerce that had been centered around the Great Lakes would be expanded beyond the borders of the U.S. with the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway in the late 1950s.

The size of the ships that transported goods also increased. The Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee was a large investor in the iron and minerals industries. The company invested in the construction of an iron ore freighter that would be the largest on the Great Lakes. The ship was named after the president of Northwestern Mutual, Edmund Fitzgerald.

When completed in 1958 the value of the Edmund Fitzgerald was estimated to be around 7 million dollars. The ship was an incredible 729 feet long, and 75 feet wide.

The launch of Edmund Fitzgerald occurred on June 7, 1958, which was a stormy one in River Rouge, Michigan. It was a grandiose event with around 15,000 spectators attending.

The launch of the Edmund Fitzgerald on June 7, 1958, at River Rouge, Michigan. Credit T. Gaertner-You Tube.

A number of “mishaps” occurred during the launch. One man suffered a heart attack after laying eyes on the ship. A few of you might have seen the newsreel where Elizabeth Fitzgerald, wife of Edmund, made 3 attempts to christen the ship by hitting it with a bottle of champagne before the bottle finally broke.

When launched, the ship created a large wave that threw water onto some of the spectators and the ship crashed into a pier.

For seventeen years Edmund Fitzgerald carried taconite from mines near Duluth, Minnesota, to iron works in Detroit, Toledo, and other ports. The ship was dubbed “The Titanic” of the Great Lakes.

Ill-Fated Voyage

Edmund Fitzgerald departed Superior Wisconsin just after 2 p.m. on November 9, 1975, on its way to a steel mill near Detroit, Michigan, carrying a cargo of iron ore pellets. The captain was Ernest McSorley. A round trip on this route usually took about ve days.

In the late afternoon, the ship joined another freighter, the Arthur M. Anderson that was headed for Gary, Indiana.

The National Weather Service had been tracking a storm that was located over Kansas early in the morning and it was moving rather quickly to the northeast. The storm was intensifying rapidly, however, and was forecast to pass just south of Lake Superior on its way to Canada,

There was another ship on Lake Superior at that time. Captain Dudley J. Paquette of Wilfred Sykes predicted that a major storm would directly cross Lake Superior. Captain Dudley chose a route that took advantage of the protection offered by the lake’s north shore in order to avoid the worst effects of the storm.

As the storm became more fierce, the National Weather Service updated its forecast at 7:00 p.m. and issued gale warnings for all of Lake Superior. Edmund Fitzgerald and Arthur Anderson changed course northward seeking shelter along the Ontario coast. An observation from Edmund Fitzgerald reported winds to 60 mph and waves up to 10 feet high.

It became apparent that the U.S. Weather Bureau, as the agency was called in those days, was struggling to keep up with the storm. At 2:00 a.m. on November 10th gale warnings were upgraded to storm warnings. Edmund Fitzgerald has been following Arthur Anderson but it then pulled ahead of it.

On November 10th The winds shifted dramatically and rain changed to snow. Winds then gusted over hurricane force and visibilities went down to zero.

Any eyewitnesses to the event will be from Arthur Anderson. An article in petoskynews.com featured a crew member of that ship and his recollections.

Ed Belanger was a 20-year-old cadet at Great Lakes Maritime Academy in Traverse City and he was receiving training aboard the Arthur M. Anderson at that time.

According to Belanger, around 5 p.m. on November 9th, their ship was joined in their eastbound journey by Edmund Fitzgerald, which was heading for a steel mill on Zug Island, near Detroit.

“It was a nice, calm day when we started out,” Belanger said. However, the weather grew steadily worse as the day progressed.

At 1 a.m. on Monday, Nov. 10, the storm became much worse. Edmund Fitzgerald reported winds of 60 miles an hour. Waves were reaching 10 feet.

The crew of Arthur Anderson would walk the full 740-foot length of the ship holding onto the sides of the hall to steady themselves in the tossing vessel.

The Edmund Fitzgerald had been traveling faster than the Anderson and remained well ahead of it. As the weather grew worse, the Fitzgerald slowed, so the ships could keep within sight of each other.

From the bridge, Belanger could see the stack at the forward section of the ship pitch as it rolled over waves. When squalls came through, they sometimes couldn’t even see the stack at all. Ten-foot waves would come crashing down upon the deck of the Anderson.

The storm eased up for a brief period on November 10th as the ships passed through the center of the storm.

With snow reducing visibilities down to zero at times, the Anderson lost sight of the Fitzgerald. The squalls upset the ship’s radar and other equipment.

By late afternoon, winds had increased with gusts to 86 miles an hour.

Waves rose, and Belanger recalls times when they could see 35-foot waves towering over the bridge approaching them.

“At times, we couldn’t see anything below us as we rode the crest of the waves,” he said.

The captain of the Anderson, Jesse B. Cooper, received a radio transmission at 3:30 p.m. from Captain Ernest M. McSorley of the Fitzgerald that the ship was taking on water. It had lost two vent covers and a fence railing.

Then, at 4:10 p.m., the Anderson received another transmission. The Fitzgerald had lost radar. It needed the Anderson to be its eyes.

Cooper contacted the Fitzgerald for the last time at 7:10 p.m. The final words from McSorley were, “We are holding our own.”

Captain Cooper tried alerting the Coast Guard as early as 7:39 p.m. when attempts to contact the Fitzgerald by radio failed, but he couldn’t speak to the officer on duty until 7:54 p.m. At around 9 p.m., with search and rescue crews unavailable, the Coast Guard asked the Anderson to turn around and look for survivors.

“Our captain told us to turn back around,” Belanger said. “What else could we do? They were our brothers out there. If our ship went down, wouldn’t we want them to come looking for us? So, we picked ourselves up by our bootstraps and kept going. It took us two hours to reach the site where the Fitz went down.”

Another ship, the SS William Clay Ford, which was also in the area, was the first to find debris and a lifeboat.

The Anderson found other pieces of debris, which they brought on board to be identified later. But no trace of Fitzgerald’s crew was found.

In the end, a crew of 29 lost their lives in the storm near Whitefish Bay. The victims ranged in age from 20-year-old watchman Karl A. Peckol to Captain McSorley, 63 years old who was planning his retirement,

A map indicating the Estimated track of Edmund Fitzgerald (red)and Arthur M. Anderson(blue) on September 9-10, 1975. Map Credit- American Meteorological Society.

Search For The Wreckage

A U.S. Navy aircraft, piloted by Lt. George Conner and equipped to detect magnetic anomalies usually associated with submarines, found the wreck on November 14, 1975. Edmund Fitzgerald lay about 15 miles west of Deadman’s Cove, Ontario, 17 miles from the entrance to Whitefish Bay to the southeast, in Canadian waters close to the international boundary at a depth of 530 feet.

In 1980, during a Lake Superior research dive expedition, marine explorer Jean Cousteau the son of Jacques Cousteau sent two divers from the Calypso in the first manned submersible dive to the Edmund. Although the dive team drew no final conclusions, they speculated that Edmund Fitzgerald had broken up on the surface.

In 1994 a dive team found the remains of a crew member partly dressed in coveralls and wearing a life jacket lying face up on the lake bottom alongside the bow of the ship, indicating that he was aware of the possibility of sinking. They concluded that “massive and advancing structural failure” caused Edmund Fitzgerald to break apart on the surface and sink.

Why Did The Edmund Fitzgerald sink?

The storm was intense, and the weather was awful with howling winds and driving rain, followed by snow. The waves were high but there were several other storms on Lake Superior that matched the ferocity of this one. The “sister” ship, Arthur M. Anderson had survived this storm survived after all.

There have been a number of theories as to what ultimately caused the Edmund Fitzgerald to sink. The weather was certainly a factor. I’ll list some (without going into details). Keep in mind that the sheer weight of Edmund Fitzgerald caused it to sit low in the water and that would allow more water to inundate the craft if there were any problems with the hatches.

1) Water poured quickly into the ship due to faulty hatches. 2) The ship hit a shoal which caused catastrophic damage. 3) The ship wasn’t well maintained, was overused, and carried too much weight. 4) Structural failure. 5) Rogue wave (over 25 feet high tore the ship in half). 6) Topside damage – Historian and mariner Mark Thompson believes that something broke loose from the ship’s deck. He theorized that the loss of the vents resulted in the flooding of two ballast tanks or a ballast tank and a walking tunnel that caused the ship to list (tilt to tale on water). Thompson further conjectured that damage more extensive than Captain McSorley could detect in the pilothouse let water flood the cargo hold.

Whatever happened probably did so quickly, since there was no distress signal or communication issued.

Weather Conditions

On November 8, 1975, a wave of low pressure emerged from the Rockies. A 7 a.m. on November 9th, an area of low pressure (1000 millibars) was located over Kansas and it was moving to the northeast.

A map indicating the track of the “Edmund Fitzgerald” storm. Pressure fell from 1000 mb to 982 mb. It later fell to 978 mb in Canada,

Conditions aloft indicated a deepening trough of low pressure moving out of the Rockies. The trough was responsible for the rapid intensification of the storm and its movement was eastward.

A 500 millibar weather map for November 9th, 1975 indicated a deepening trough over the Rockies (purple). Credit -Daily Weather Maps-NOAA Central Library.

The wind and waves were by-products of the storm’s power. The wind shift that was observed on the 10th resulted from the low passing over Lake Superior and up into Canada. The brief respite in the wind was probably because the ships passed through the center of the low pressure. Cold air rushed in behind the low and changed rain to snow.

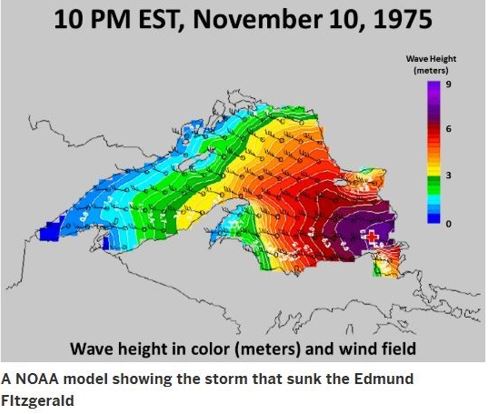

In 2006 the NWS ran a computer model of wind direction and speed of the storm with high resolution. The strongest winds were in the three-hour period just before and after the sinking. A large area of southeast Lake Superior had 50 mph winds or greater. Waves were reported at 25 feet at that time.

Each year, on November 10th there is a memorial ceremony for the Edmund Fitzgerald at the Shipwreck Museum at Whitefish Point in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. It begins at 7:00 pm, which is the moment the ill-fated ship was lost forever

The storm remains “legendary” The exact cause of the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald will likely never be known. The ship, along with the bodies of the dead, remains at the bottom of Lake Superior to this day.