It was Easter Monday in April of 1360, when the army of the English crown was prepared to launch an attack on the French at Chartres, just southwest of Paris, France. In a short period of time, the English invaders were brought to their knees, begging God for mercy. They were physically and emotionally defeated. The victory did not involve swords or arrows, spears, or boulders. This victory was not won by the French. The English defeat emanated from the sky in the form of a most incredible storm.

Hundred Years’ War

Since I will be describing a weather event, I will try not to get too tied up in history, but it is interesting. The pending attack that I mentioned above was part of what was to be known in the history books as the “Hundred Years’ War”.

England and France, much like cats and dogs, were involved in one conflict or another over many centuries. The Hundred Years’ War was fought in spurts from 1337 to 1453.

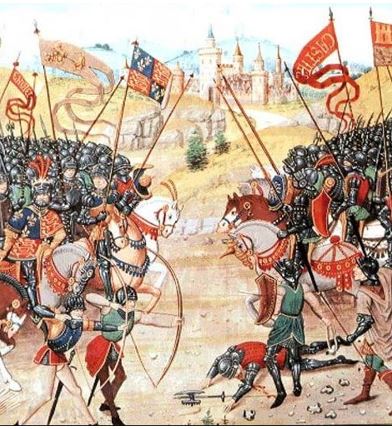

An artist’s depiction of a battle scene from the Hundred Years’ War between England and France. Image Credit-Public Domain

The cause of the war had to do with the death of a French monarch Charles IV who died without a male heir. During that period of time, women were not allowed to ascend to the throne. The wife of the deceased king, Isabella wanted her nephew, King Edward III of England to take the crown.

This didn’t sit well in France so Phillip VI, who was part of the French royal family became king. The Hundred Years’ War was basically a power struggle for the rule of France.

King Edward III of England was bound and determined to conquer France, which he deemed rightfully his. At the time, residents of England lived under a feudal system that separated them into classes from kings and lords down to peasants and serfs.

In 1346, King Edward III commanded every man-at-arms to join the army or send a substitute.

Feudal lords were commanded to send men-at-arms and archers proportionately to their income. Many of them came from peasants or serfs. If you didn’t obey this command, you were sent to prison.

In October of 1359, Edward took a massive army of 10,000 men across the English Channel to Calais in France. The invading force consisted of 4,000 men-at-arms, 5,000 mounted archers, and over 700 mercenaries from the European Continent.

While the English forces went into an offensive attack mode, the French did just the opposite. They actually refused to directly fight the invaders but chose instead to stay put behind the protective walls of each town during the winter months. Meanwhile, Edward and his forces ravaged and pillaged the French countryside.

A “Stormy” Twist Of Fate

In April of 1360, The invading forces set their sights on Paris. King Edward felt confident that victory would be theirs and France would bow to his rule. With him, Edward had some of his best lieutenants, such as the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Lancaster, who had won many victories over the years.

As the army reached Paris, everything was set for battle. Once again. the French, led by Charles Dauphne realizing that they had no chance for victory, refused to engage in battle.

Edward saw that it wasn’t possible to breach the French defense of Paris, so the army moved on while laying waste to the countryside. Instead, Edward moved to the southwest toward the cathedral city of Chartres.

On Easter Monday, Edward’s army arrived at Chartres. The French refused battle and took shelter behind their fortifications. Without much of a force to fight, it appeared that the French would be overwhelmed by the English siege. So, the old strategy of “lay low and hope for a miracle” was implemented again.

Nightfall, on what would be a fateful evening, was fast approaching so the English army began to settle down and camp just outside of Chartres. By many accounts, soon after, the skies became angry, the wind became vicious, the temperature plummeted quickly, and bolts of lightning became more frequent. A cold, and wind-driven rain was falling when all of a sudden large balls of ice began to fall from the sky and pelted the army and their horses. The French had received their “miracle”.

One soldier described the event this way: ” a foul day full of myst and hayle so that men died on horseback”. From the Chronicles of Jean Froissart was this account :

“For an accident befell Edward III and all of his army, who were then before Chartres, that much humbled him and bent his courage.” “There happened such a storm and violent tempest of thunder and hail, which fell on the English army, that it seemed as if the world was coming to an end. The hailstones were so large as to kill men and beasts, and the boldest were frightened.”

The storm lasted less than an hour. All told, estimated casualties from the storm were nearly 1,000 soldiers dead, along with 6,000 horses. Two soldiers died after being struck by lightning.

Image of a plate showing King Edward III, on Black Monday .. in the background you can see the thunders that changed the course of history. Image Credit- (“The History of that Victorious Monarch Edward III” by Joshua Barnes)

Edward was convinced that the storm was a sign from God as punishment for the pillaging of the French countryside during Lent. He turned toward the church of Our Lady at Chartres and vowed to the Virgin Mary that he would accept terms of peace from the French.

After some back-and-forth communication, the French wasted no time coming up with peace initiatives. In fact on the very next day, the French sent representative Androuin de la Roche with a proposal for a treaty.

Edward left his lieutenants to negotiate with the French at a nearby town of Bretigny and he withdrew his army. A treaty was negotiated and signed. Edward would renounce his claim to the French throne but he would have full sovereignty over Aquitaine, Poitou, and Calais. The result is seen in the map below.

A map of France following the Treaty of Bretigny. The green area denotes French control while the pink denotes English control. Map Credit -Public Domain

The Treaty Of Bretigny ended what was called the first phase of the Hundred Years War. The peace lasted nearly a decade before hostilities resumed once again.

Odds And Ends

There are plenty of questions surrounding this weather event. How can a hailstorm kill 1,000 men and 6,000 horses? Several publications indicate that this is exactly what happened but some chronicles over the centuries indicate that some men could have died from exposure (hypothermia) to the severe elements. Others indicate that the storm itself spooked hundreds of horses leading to a deadly stampede.

Since I wasn’t there I can only conjecture. The storm certainly took the English army by surprise the army was stationed outside of the town and they were extremely vulnerable in the open fields.

I have no idea about the exact size of the hailstones but they certainly were damaging and deadly. I would tend to think that this incredible death toll was a result of all of the above factors that happened to come together over a short period of time. It was enough to scare the King of England into submission.

This weather event became documented in history books and chronicles as “Black Monday”. It became engraved in English history, with trepidation, for centuries to come in England. Over two centuries later, William Shakespeare made a reference to Black Monday in The Merchant Of Venice (Act 2, Scene 5) in a conversation between Launcelot Gobbo and Shylock. “And they have conspired together. I will not say you shall see a mosque, but if you do then it was not for nothing that my nose fell a-bleeding on Black Monday last at six o’clock in’ the’ morning falling out that year on Ash Wednesday was four years in the’ afternoon.”

Meteorological Conditions

I often like to recreate what weather conditions were like, sometimes on a map. for historical events. With only “hearsay” information, the task would be impossible.

We do know that there was a terrible storm that didn’t last that long. From word of mouth, it was chronicled to have featured lightning, driving rain, rapidly falling temperatures incredibly large hail.

It would be over three centuries before even rudimentary weather instruments like the thermometer and the barometer were invented and used.

All that I know is that the atmospheric dynamics aloft must have been ideal to create such an event. If some of my “fellow meteorologists” have any theories, feel free to chime in.

The English/British armies certainly did have some bad luck with the weather at times through the centuries. In my article about the Battle of Trenton during the Revolutionary War, a nor’easter aided the Revolutionary Army against the British mercenaries (Hessians).

Before that, a dense fog around New York City offered cover to Washington’s army for an escape so they could avoid a battle that they were doomed to lose.

During the D-Day invasion in World War II, weather forecast teams, which included a college professor of mine, were able to forecast a break in a prolonged period of wind and rain which was fortuitous for the Allies.

I guess that if you are involved in so many wars over the centuries, you are bound to have some bad weather luck, but it can go both ways.