On November 26, 1703 (Julian Calendar) a storm of epic proportions tore through the countryside of England and Wales. There were also incredible losses of ships and men at sea. The storm in inflicted catastrophic damage across the most populated areas of England, especially in London. At least 8,000 and perhaps up to 15,000 people lost their lives in one of the worst extratropical storms in recorded history.

Historical Background

Life was rough in England as the 18th century began. There were basically two classes the royal rich and the poor. London was crowded with a population of around 600,000 and is was quite dusty and disease-ridden. For every 1,000 births, about half did not survive until the age of two.

Most of the population was engaged in agriculture, there were also craftsmen who were often had their own specialty. The British Navy ramped up significantly around 1700 as the War Of Spanish Succession had begun. Many men joined the Navy or they were involved in shipbuilding for the rapidly expanding fleet.

After a wet summer, the autumn of 1703 was particularly stormy. In mid-November, a series of storms moved through Britain knocking down chimneys in London and sinking several ships off the coast. Little did the residents know that there would be a storm coming of such fury that it would be written about for centuries.

The Great Storm of 1703

On November 25, 1703, the English Channel was full of ships. The series of storms storm that I mentioned earlier, produced westerly winds and ships that were full of goods couldn’t sail with westerly winds in the Channel. In addition, there were ships from the Royal Navy stuck there as well. The Navy had been preparing for an assault on the coastal city of Cádiz in Spain.

On November 26th the skies darkened across the English Channel and by late in the day the wind and rain began to intensify. It didn’t take long for the storm to unleash its full fury. According to the publication islandnet.com, the Reverend Thomas Crest described this pic storm as it ravaged the English Channel.

“Sir, upon the evening of Friday, Nov. 26, 1703, the wind was very high, but about midnight it broke out with a more than wonted Violence, and so continued till near break of day. It ended a N.W. Wind, tho’ about 3 in the Morning it was at S.W. The loudest cracks I observed of it, were somewhat before 4 of the Clock; we had here the common Calamity of Houses shatter’d and Trees thrown down.”

“But the Wind throwing the Tyde very strongly into the Severn, and so into the Wye on which Chepstow is situated. And the Fresh in Wye meeting with a Rampant tide, over owed the lower part of our Town. It came into several Houses about 4 foot [1.2 m] high, rather more; the greatest damage sustained in Houses was by the makers of Salt, perhaps their loss might amount to near £200.”

This print depicts a British Naval fleet off the coast of Dunkirk during the Great storm of 1703. Print Credit-Unknown Author-Pubic Domain.

This print depicts a British Naval fleet off the coast of Dunkirk during the Great storm of 1703. Print Credit-Unknown Author-Pubic Domain.

A ten-foot storm surge inundated the town of Bristol and damage was estimated at 100,000 pounds. The surge backed into the Severn River and wiped out a wooden bridge. The resultant flooding destroyed valuable agricultural land and killed livestock. Many cows were killed. One cow was found hanging from a tree. At high tide, around 15,000 sheep were drowned.

In Anglia, winds were estimated to be greater than 100 miles per hour. The storm wreaked havoc across the countryside. The wind was so strong that the blades of windmills were whirring at a high rate of speed. Frictional heating allowed them to catch on fire. Barns, sheds, and stables all over were reduced to ruin. Humans and animals were literally picked up and launched by the wind.

In Brighton, the wind destroyed Sherman’s quarter, tenements, stores, and cottages. The town of Norfolk reported several casualties.

The Isle of Wight looked completely white as a spray as salt from sea spray had covered the land. This was also true in areas around the English Channel. For a lengthy period of time after the storm, cows and sheep refused to graze off the salty pastures.

Hundreds of people drowned in flooding on the Somerset Levels, along with thousands of sheep and cattle. One ship was found 15 miles inland. At Wells, Bishop Richard Kidder and his wife were killed when two chimney stacks fell on them while they were sleeping. Major damage occurred to the southwest tower of Llandaff Cathedral at Cardiff in Wales. The Eddystone Lighthouse off Plymouth was also completely destroyed killing its six occupants. The city of Portsmouth incurred inconceivable damage.

This print from Robert Chambers in 1869 depicts the destruction of the Eddystone Lighthouse during The Great Storm of 1703. Public Domain.

In London, the storm blew down around 2,000 chimney stacks and many people were killed in their beds while sleeping. There was costly roof damage inflicted on Westminister Abbey. The ferocious wind actually blew fish out of the ponds and onto the banks in London’s St James’s Park. Birds were beaten into the ground. Part of the Tower of London was blown to the ground. On the Thames River, around 700 ships were thrown together like matchsticks in the Pool of London, near the London Bridge. Churches all over the city lost spires and towers. There was considerable loss of life across the city.

Queen Anne and members of the royal family were forced to take refuge in the cellars of St James’s Palace to avoid its collapsing chimneys and roof.

In addition to all of the death and destruction over land, there were also incredible losses at sea. In fact, most of the deaths occurred at sea with the toll estimated to be around 6,000. As mentioned earlier, there were many naval vessels that were stuck in the English Channel when the storm struck. The Royal Navy had three fleets that were ready to attack Spain. The combination of wind and storm surge destroyed thirteen Royal Navy ships and killed 1,500 seamen. Off the coast of Kent, 130 vessels were totally destroyed, including 100 merchant ships.

A number of admirals chronicled the storm. Here is one account that was featured in a publication from bbc.com.

“It was so severe, none of these poor captains had ever experienced it before, so they didn’t have any yardsticks to base the description on,” says Wheeler, who studied Royal Navy logbooks at length. “One gave up and just wrote ‘a most violent storm’ and left it at that, for sheer want of anything more he could say.”

Overall, the death toll from the Great Storm of 1703 was estimated to be around 8,000 but some think that it could have been as high as 15,000. The storm is considered to be the worst in the history of Britain. The storm also in inflicted considerable damage to the northern coast of France, before moving eastward to Belgium, northern Germany, and Scandinavia.

Odds And Ends

The storm was considered by most of the population to be a sign of God’s anger in Britain. Over a month later, Queen Anne decreed that there would be a day of recognition and fasting. The storm was a topic of sermons in the churches into the 1800s.

The widespread destruction resulted in much work but considerable profit for the bricklayers, tilers, and carpenters and the cost of labor doubled. The price of building tiles jumped to four to five times their pre-storm costs. Parliament debated how to replace the many naval vessels lost, wondering if stranded and rescued wrecks could be salvaged.

The total damage across the nation and to the British Navy was assessed at nearly 4 million pounds. An estimated 300,000 trees were split or uprooted. Four hundred windmills and eight to nine hundred houses were destroyed, and over a hundred churches severely damaged.

The storm resulted in a surge in English journalism as it was the first great weather event to be a national news story. Noted author Daniel Dafoe set out to collect various stories about the storm. He placed an advertisement in the London Gazette of 2–6 December 1703, to request that men write to him with their recollections.

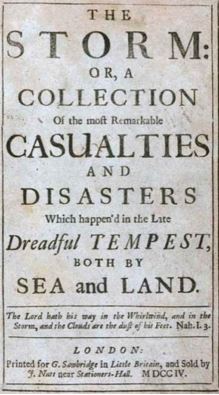

In 1704 his book “The Storm” was published. Defoe thought that the storm was God’s punishment for England’s poor performance against Catholic armies during the War of the Spanish Succession.

This image shows the cover of Daniel Dafoe’s book “The Storm”. A collection of stories gathered by witnesses of the Great Storm of 1703 in Britain. Public Domain.

Although most of the population was convinced that the storm was a sign from God, there were some in the scientific community who recognized that major weather events deserved more study with the hope of someday predicting them to some extent.

There were reports a week earlier than a powerful storm had impacted the East Coast of America from the Carolinas to New England. Was it possible that this storm had ‘tropical roots”? There were barometers back then and a pressure of 973 millibars (28.7 inches) was measured around the English Channel and there is some indication that the pressure bottomed out around 950 millibars (28.05 inches) in the Midlands. The storm has been likened to a Category 2 hurricane. There were reports of lightning and loud thunder that accompanied the storm.

Hubert Lamb who initiated the Climate Research Unit at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, UK, studied the storm in collaboration with Knud Frydendahl of the Danish Meteorological Institute. From all that was written and various observations, there could have been one low-pressure system passing through the northern coast of Scotland, but a second low gained strength in southern England, perhaps on a triple point (between a warm and cold front). I attempted to recreate a surface weather map for that date in the featured image of this article.

Over three hundred years later, The Great Storm of 1703 remains a benchmark by which all major storms to hit Great Britain are compared.