In the late evening of August 17, 1969, Hurricane Camille made landfall near Pass Christian Mississippi. This Category 5 monster is the second strongest hurricane to strike the mainland of the United States. With wind gusts perhaps up to 200 mph and a storm surge of over 24 feet, many residents that didn’t evacuate were killed, Inland, over two feet of rain killed many more in Virginia.

There have been several events that I have written about that I can remember or I was involved with forecasting. Even though I was a weather fanatic and ready to enter my senior year of high school, I wasn’t aware of this event until a week after it struck.

I had won a national award (Navy Science Cruiser) for my science fair project and got to spend five days, with other award winners, at a naval base in Newport, Rhode Island and I was there as Camille made landfall. Without access to TV or newspapers, I had no idea about the magnitude and impact of this hurricane.

Track Across The Atlantic

Hurricane Camille was a “classic” Cape Verde storm. On August 5, 1969, a tropical wave came off the African Coast. Atmospheric conditions weren’t favorable for strengthening and the wave continues to track westward across the Atlantic.

On August 14th, more convection (thunderstorm activity) began to appear in the vicinity of the tropical wave. On August 14th, hurricane hunters flew out to investigate. Later in the day, the aircraft found a low-level circulation and winds that were high enough to justify naming this a tropical storm. The “C” name was Camille. There is a story attached to the name that I will discuss later.

Camille was named when it was centered about 60 miles west of Grand Cayman Island as it was turning more toward the northwest. Wind shear continued to decline and that made conditions more favorable for Camille to strengthen. That’s exactly what occurred as the central pressure of Camille dropped over 40 millibars in only 24 hours.

Camille became a hurricane on the morning of August 14th around 60 miles south-southeast of Pinar del Rio, Cuba on the island’s western tip. Camille continued to rapidly intensify and Camille became a “Major” Category 3 hurricane later that day.

Camille produced extensive damage in western Cuba, mainly due to heavy rain and massive flooding. Around 20,000 became homeless and there were at least five fatalities. The damage was estimated to be around five million (1969) dollars.

Eying The Gulf Coast

As Camille passed over Cuba, it weakened but everything changed in a hurry as it came back out over the Gulf of Mexico. With a track toward the northwest, Camille became stronger with maximum sustained winds of 140 mph on August 16th. As it left Cuba, the forecast track from the National Hurricane Center indicated that the forecast was for Camille to take more of a turn to the northeast and that would favor a landfall in the Florida Panhandle. Subsequent forecasts kept sliding the landfall to the west but Camille continued to track west of the updated forecasts each time.

Camille didn’t stop intensifying and on August, 17th maximum sustained winds were up to 160 mph making Camille a Category 5 hurricane. Later in the day, Camille was centered about 100 miles southeast of the mouth of the Mississippi River with maximum sustained winds of an incredible 190 mph and a central pressure of 905 millibars.

New Orleans radar shows Hurricane Camille as it approached the Mississippi Coast on August 17, 1969. Image Credit- ESSA/NOAA

Late that evening, Camille made landfall near Pass Christian, Mississippi with unimanageble force. All wind instruments were destroyed and all power was lost so we will never know the exact sustained winds at landfall but some estimates indicated that wind gusts could have reached 200 mph.

Gulf Coast Impacts – Wind And Surge

Camille inflicted massive amounts of damage to the barrier islands and along the Gulf Coast from Louisiana to Alabama. The storm surge along the Mississippi Coast reached an incredible 24.6 feet and inundated over 800,000 acres of land in Louisiana. The surge later crashed over the seawall along the Mississippi Coast and pushed over four blocks inland with tons of debris. To the east, nearly three-quarters of Dauphin Island, Alabama was inundated.

Many roads, including a large section of Highway 90 along the Gulf Coast were closed for days and in some cases, weeks.

The photo shows extensive storm surge damage to Highway 90 in Mississippi from Hurricane Camille in August of 1969. Photo Credit-ESSA/NOAA

Rain and powerful winds split Ship’s Island off the Mississippi Coast and cut the Chandeleur Islands off Louisiana.

There was one “iconic” before and after photo of the Richelieu Manor Apartments that was slammed by the eyewall of Camille and the tremendous storm surge as it made landfall. There was also a story that went along with the pictures. According to the story, 24 people held a “hurricane party” on the third floor. The story goes on to say that the storm surge destroyed the building and killed all but one person. We do know that the building was destroyed but accounts of the party are varied and it’s not clear whether there actually was a party.

This photo shows the Richelieu Manor Apartments before Hurricane Camille struck. Photo Credit-ESSA/NOAA

This photo shows the Richelieu Manor Apartments after Hurricane Camille struck. Photo Credit-ESSA/NOAA

There was extensive damage to homes and businesses in the vicinity of the coast in Biloxi and Gulfport in Mississippi. Hotels and restaurants were totally destroyed. Fires were fought with hard suction hoses since the fire trucks were submerged.

Many people had to move to higher floors of their homes, even well inland from the coast to avoid drowning. Some residents described a deafening wind but they could hear the sound of windows breaking all around them.

This photo shows catastrophic storm surge damage near Biloxi, Mississippi from Hurricane Camille in August of 1969. Photo Credit-NOAA

Crop damage was extensive across southeast Mississippi with the total destruction of many pecan orchards. Crop damage across south Alabama was limited to Baldwin, Mobile, and western Washington Counties.

Pecan, soybean, and corn crops were damaged or destroyed. Pecan damage was extensive and approximately 20,000 acres of corn were attended. It was estimated that 90% of crop damage across the area was due to the wind while 10% was due to the rain.

Total property damage for the Florida Panhandle, including beach erosion and crop losses, was estimated near 500,000 (1969) dollars with the major portion of the damage in Escambia and Santa Rosa Counties.

It was fortunate that rainfall totals in southern Mississippi and southeast Louisiana were held down to the 5-7 inch level because the storm was moving fairly at a good pace as it moved inland.

Over 100 fatalities were tied to the storm in the Gulf region.

Inland Impacts – Heavy Rain And Flash Flooding

Fortunately, Hurricane Camille weakened pretty quickly after moving inland. By midday on August, 16th Camille was downgraded to a tropical storm and it became a tropical depression as the center moved into Tennessee. After reaching Kentucky it moved eastward.

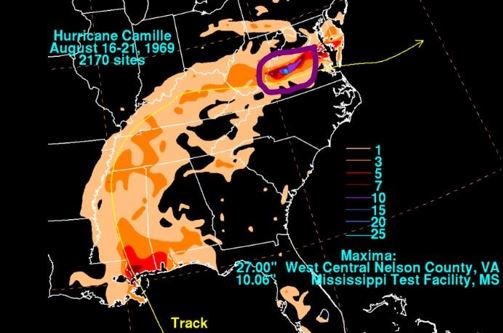

Unfortunately, the remnants of Camille dumped extremely heavy amounts of rain as it crossed the Appalachians into West Virginia and Virginia. High tropical moisture and elevation don’t mix very well. Rainfall amounts generally ranged from 12 to 20 inches over these areas. There was one report of 27 inches in Nelson County, Virginia. Much of the rain in Virginia fell in less than six hours.

This map indicates the rainfall totals from Hurricane Camille in August of 1969 (highlighting the excessive rain in VA). Map Credit-NOAA.

Needless to say, that kind of rainfall in a relatively short period of time can trigger extreme flash flooding along rivers and creeks in the area. Over 130 bridges were washed out and entire communities were submerged in water, especially in Nelson County and the surrounding area.

Rainfall was so heavy that reports were received of birds drowning in trees, cows floating down Hatt Creek, and survivors having to cup their hands around their mouths and nose in order to breathe

Many rivers in Virginia and West Virginia set records for peak flood stages, causing numerous mudslides along mountainsides.

All told, over 5,600 homes were destroyed and nearly 14,000 had major damage. There were nearly 9,000 injuries and over 150 fatalities. Overall damage was estimated to be around 140 million (1969) dollars.

Aftermath

According to Wikipedia, Many federal, state, and local agencies and volunteer organizations responded in the following days. The Office of Emergency Preparedness, provided 76 million dollars to administer and coordinate disaster relief programs.

Food and shelter were available the day after the storm. On 19 August, parts of Mississippi and Louisiana were declared major disaster areas and became eligible for federal disaster relief funds. President Nixon ordered 1450 regular troops and 800 United States Army Engineers into the area to bring tons of food, vehicles, and aircraft.

Many injured residents and others who needed medical attention were airlifted to inland cities like Jackson. The Federal Power Commission helped fully return power to affected areas by November 25th, 1969.

The Coast Guard (then under the Department of Transportation), Air Force, Army, Army Corps of Engineers, Navy Seabees, and Marine Corps all helped with evacuations, search and rescue, clearing debris, and distribution of food. The Department of Defense contributed $34 million and 16,500 military troops overall to the recovery. The Department of Health provided 4 million dollars towards medicine, vaccines, and other health-related needs.

Odds and Ends (From NOAA)

The devastation of Camille inspired the implementation of the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale after Gulf Coast residents commented that the hurricane warnings were insufficient in conveying the expected intensity of storms.

Hurricane Camille generated waves in the Gulf of Mexico that were at least 21 m (70 ft) in height.

Camille created the highest storm surge recorded at that time in the Atlantic Basin at 7.5 m (24.6 ft). This measurement was based upon high water marks inside the three surviving buildings (the V.F.W. Club, the Avalon Theatre, and one house) and debris lines in Pass Christian, MS. This record value was surpassed in 2005 by the 8.47 m (27.8 ft) surge produced by Hurricane Katrina.

As evacuees returned to Mississippi, the Governor declared martial law, blocking highways into the damaged areas, creating a 6 PM to 6 AM curfew, and opening dormitories at the University of Southern Mississippi and rooms at the Robert E. Lee Hotel to shelter those who lost their homes.

Camille forced the Mississippi River to flow backward from its mouth in Venice, LA to a point north of New Orleans, LA, a distance of 200 km (125 mi) along its track. From there, the river backed up an additional 190 km (120 mi) to a point north of Baton Rouge.

Like other catastrophic Category 5 hurricanes, including Hurricane Andrew (1992) and the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane, the diameter of Camille was relatively small. A report from a reconnaissance aircraft as the hurricane was near peak intensity described winds of more than 115 mph just 30 to 40 miles from the eye.

(From NWS Mobile) :

August 17, 1969

450 pm – A hangar wall was blown down at the Fairhope Airport in Fairhope, AL

530 pm – Tornado reported in Waynesboro, MS

600 pm – Streets completely covered with water in Bayou La Batre, AL

630 pm – Tornado reported in Pensacola, FL earlier in the afternoon

930 pm – Violent winds observed along the coast

1000 pm – 62 mph wind observed in Mobile, AL

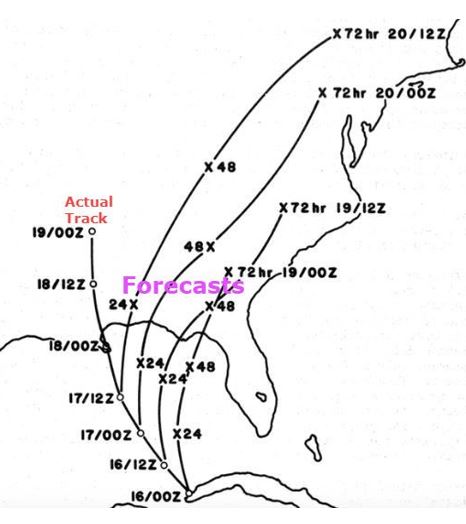

Hurricane forecasting was very hit-and-miss back then. There were only a couple of computer models and they were crude and not constructed to handle the tropics. I’ll show you the NHC forecasts from the time and the forecast at regular intervals thereafter(48-72 hour forecasts). Most forecasters thought that Camille would curve to the northeast and make landfall in the Florida Panhandle but Camille continued to track west of their forecast tracks.

This image shows NHC forecasts for Hurricane Camille from the time it was over the western tip of Cuba.

This image shows NHC forecasts for Hurricane Camille from the time it was over the western tip of Cuba.

Far left was the actual track of Camille. Image Credit- Robert Simpson-Southern Regional Technical Memorandum -WBTM

An upper-level trough finally steered the remnants of Camille eastward through Virginia and into the Atlantic. Camille actually intensified to a tropical storm again once it came back over water but it continued to move away from the U.S.

There is an interesting story surrounding the name “Camille”. Other ”C” hurricanes like Carla and Carol were retired so a “C” name was needed for the 1969 season.

At that time, the senior hurricane forecaster at NHC was John Hope, who I have the privilege to work with for many years at the Weather Channel. His daughter, Camille was doing a high school project on hurricanes and long-term trends and Dr. Canner Miller at NHC mentored her with the project. Dr. Miller was very impressed with Camille’s work so Camille was added to the list of hurricane names for that season (little did they know).

I met Camille many years later at an anniversary celebration for the Weather Channel so I guess that I have somewhat of a connection to this event after all.